|

| September 23, 2014 | Volume 10 Issue 36 |

Designfax weekly eMagazine

Archives

Partners

Manufacturing Center

Product Spotlight

Modern Applications News

Metalworking Ideas For

Today's Job Shops

Tooling and Production

Strategies for large

metalworking plants

Novel capability enables first test of real turbine engine conditions

By Tona Kunz, Argonne National Laboratory

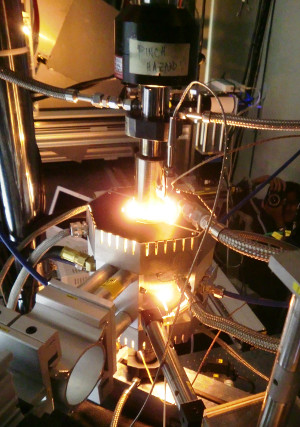

A mechanical stress testing setup with a custom-built compact furnace and cooling system that mimic extreme operating conditions on turbine engines at the Advanced Photon Source at Argonne National Laboratory. [Photo credit: DLR]

Manufacturers of turbine engines for airplanes, automobiles, and electric-generation plants could expedite the development of more durable, energy-efficient turbine blades thanks to a partnership between the U.S. Department of Energy's Argonne National Laboratory, the German Aerospace Center, and the universities of Central Florida and Cleveland State.

The ability to operate turbine blades at higher temperatures improves efficiency and reduces energy costs. For example, energy companies estimate that raising the operating temperature by 1 percent at a single electric-generation facility can save up to $20 million a year. In order to achieve the highest temperatures of 1,832 F in engines, metallic turbine blades are coated with ceramic thermal-barrier coatings and actively air cooled, which together allow for operating temperatures exceeding the metal's melting point. Adding to these extreme conditions, during high-temperature operation, blade rotation induces thermo-mechanical stresses throughout the blade components.

Because of the difficulty of monitoring engines in operation, most manufacturers test blades either after flight or rely on simulated tests to give them the data on how the various coatings on the blades are performing. Until now, creating an accurate simulation has been out of reach, but the team knew that if they could build it, industry would come calling.

"While the idea sounded impossible, we had a team of willing collaborators with complementary skills as well as excellent students who were motivated to take on the challenge," said Seetha Raghavan, an associate professor of mechanical and aerospace engineering at the University of Central Florida and a co-author on the team's paper outlining the novel technique in the July issue of Nature Communication.

The research team has succeeded in developing a new in-situ facility for use at Argonne's Advanced Photon Source (APS) that, for the first time, accurately simulates these extreme turbine engine conditions. In particular, the Florida team developed an improved furnace system, and the German team developed a novel coolant system to add to the mechanical testing system at Sector 1 of the APS, where the high-energy X-rays (E~86 keV) were able to penetrate all layers of a coated test blade.

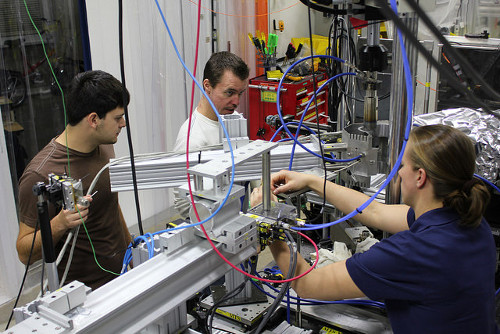

(From left) University of Central Florida Ph.D. students Albert Manero and Kevin Knipe work with Janine Wischek, head of the Mechanical Testing of Materials Group from the German Aerospace Center, to integrate the unique experimental X-ray setup at the Advanced Photon Source at Argonne National Laboratory. [Photo credit: University of Central Florida.]

This goes beyond any other in-situ capabilities to allow the influence of temperature, stress, and thermal gradients to be studied together. This enables scientists to view the microstructure and internal strain in both the substrate and thermal barrier coating system during real operating conditions and in real time -- a capability that is totally new.

The team captured high-resolution images of evolving strains; future experiments aim to pinpoint when and where defects start. This would allow for an accurate lifespan estimate on material and to improve the process for applying ceramic thermobarrier coatings. This could help industry in a couple of ways. It could potentially improve the quality of plasma spray applications and reduce the cost of the more expensive, higher quality electron beam physical vapor deposition, EBPVD, applications.

"This integrated approach allows us to simulate the engine conditions, so manufacturers are getting interested," said Jon Almer, a co-author on the publication and scientists at the APS. "I would expect the APS to remain the only place in the world with these capabilities for at least the next couple of years, if not longer."

Already, the military and two Fortune 500 companies have shown interest in conducting similar future experiments at the APS.

A proposed upgrade of the APS to become the nation's brightest high-energy synchrotron would give industry even more options. A factor of 100 increases in brightness of the X-ray beam would enable the study of more types of coatings and increase sensitivity to the micro-structural evolution of defects. Added coherence in the X-rays would reveal smaller features in the defects, potentially from today's 200-micron feature to about a 200-nanometer feature.

"Manufacturers have told us they would really appreciate that," Almer added.

In Nature Communications, the team outlined the first test of the system and reported previously unseen relationships between internal strains and thermo-mechanical operating conditions enabled by this novel experiment technique. In particular, specific operating conditions were identified that caused severe gradients, as well as undesired tensile strains in the coating layers. This previously unknown material behavior will be used to validate simulations of these operating conditions to ensure safe operating windows are maintained. Furthermore, this information can be used to improve the deposition process during manufacturing, innovate coating materials, and allow for the use of coatings at higher temperatures, which could lead to wider adoption.

"The productive efforts of this collaboration bring high-temperature materials system testing to the next level," said John Okasinski, co-author and assistant physicist in Argonne's X-ray Science Division. "It will also facilitate unique insights into thermo-mechanical states, particularly at the thermally grown oxide layer."

This work was funded by the National Science Foundation and the German Science Foundation. The APS is a DOE Office of Science User Facility.

Published September 2014

Rate this article

View our terms of use and privacy policy